Submitted for your approval: Unit 1 of ENG 4C, Barker-style. This is just the outline of course, but my plan is to make each strand a major focus for each unit. The first unit is mostly diagnostic but the focus will be on the Oral Communication strand. I’ve included links (wherever possible) to the resources I plan to use and I have also attached my course outline (planning version, not official version) so you can see how this unit fits into the whole. I know the last thing my teacher friends want to think about right now is planning but I’d love any feedback you’re willing to provide.

ENG4C Unit Plan 1

Category Archives: classroom practice

Teachers in the Movies

I wrote this a couple years ago after being forced to sit through Freedom Writers on a PD Day. I apologize to those of you who found the movie inspiring and I have nothing against Erin Gruell as a person–it’s the movie I take exception to. This top ten list is about all teacher movies–not just Freedom Writers.

TOP TEN THINGS I LEARNED ABOUT TEACHING FROM THE MOVIES

1. Teaching is a breeze because classes are never more than five minutes long

2. The bell will always ring at an appropriate time; infact, the bell will usually underscore some dramatic point you are making to your rapt audience of 25-year-olds.

3. Your students will be 25.

4. Don’t worry about the kids you can’t help; they will be edited out of your story.

5. If you’re a GOOD teacher, you will sacrifice your marriage for your students.

6. All it takes to turn a kid around is a smile and a kind word–and bribery.

7. By the end of the year, all your students will love you, hoist you up on their shoulders and perhaps address you as “Oh Captain my Captain.”

8. If you want to be a nice teacher, you will encounter opposition from all the other teachers at the school because they are ALL bitter disgruntled people who hate kids. Except you. You my friend will change the world.

9. All gang violence at the school will end if you get your class to write in diaries.

10. Oh, I have to stop at ten. Okay… 10. You will only have to teach one class, but you should–nay–you must be willing you use your own money to supply your classroom, even if that means taking on part-time jobs selling bras and working as a hotel concierge. That’s what a good teacher does.

Priorities

I’ve learned so much this year that it’s tempting to throw myself into every initiative that comes across my desk and to want to change everything about my teaching all at once.

It’s tempting.

It’s also INSANE!

So I’ve decided to set some priorities for next year, and I’m following the model that my friend Kevin shared with me, that he learned from a speaker in his Master’s class. This person held up one hand and said that he was so busy he decided that he would have five priorities (Get it? Five fingers? Five priorities. I guess you only get to have six priorities if you’re the bad guy who killed Inigo Montoya’s father, in which case you’re going to die anyway so…) not just for work, but for your life. If something doesn’t fit one of those priorities you have to say no. Easier said than done, but I’ll give it a try. I just need to figure out what my priorities are.

Well first of all, it seems important to me to make sure that my relationships with my family and friends should be at the top of my priority list.

Then health. That can be physical, mental, and spiritual.

Yikes! That only leaves three left for professional priorities!

All right, well we all know that I want to find ways to bring more web 2.0 into the classroom even if I don’t have a beautiful shiny wifi Apple-sponsored computer lab (But seriously, that would be amazing).

Two left!

Assessment and Evaluation: No big surprise there. I want to continue to refine my understanding of good assessment and evaluation practices and how to bring together the ideal and the reality in order to support students. I like this one because it encompasses a lot of other things that I’m passionate about.

One left! Well people keep asking me what my ultimate goal is in this profession. Do I want to go into admin? Do I want to go back to the board office? Do I want to go to grad school? For now, I’ve decided that my ultimate goal is to be a really really good teacher. To some people that may not sound like a terribly ambitious goal, but it is to me. I think it’s easy to become complacent in this profession. I think that you have to keep pushing yourself to get better and to continue to see yourself as a learner. I never want to have the attitude that “I’ve been doing this for 20 years; there’s nothing new anyone can tell me about teaching.” So my fifth priority is to view myself as a professional learner. That may sound a bit too vague but I know what it means.

So that’s it for now. I may come back and revise these later. Do you have any priorities or goals for next year?

I am a Nerd

I prefer the term “geek” but in this case I am a nerd. At least I’m in good company. Thanks to my pal and colleague Heather, I got to go to the lovely town of Glencoe this past Friday and see assessment guru Damian Cooper.

Damian Cooper is so passionate about the topic of Assessment for Learning that he literally bounces around the room while he’s talking. I for one particularly appreciate the fact that he comes from a secondary English background and that he’s not so far removed from the classroom that he doesn’t understand the all of the “in the trenches” realities that teachers deal with on a daily basis. He also doesn’t shy away from difficult questions. I found myself hanging on his every word.

He identified what is for me one of the biggest struggles with the assessment in Ontario: the ministry says it supports the idea of assessment for learning, but its policies and procedures don’t provide the support teachers need to implement these ideas. If we really believe that work habits such as punctuality, attendance, etc. are important, then they need to have some weight behind them. Learning skills need to show up on transcripts–otherwise they have no teeth. If a student can’t be given an academic penalty for not submitting an assignment or not submitting it on time, then there needs to be an appropriate behavioural consequence–again, something with teeth.

The part that I’m still not entirely clear on is this issue of deadlines. I understand that some students need more time than others to complete assignments. But I also understand that if I’m told I can hand something in between October 1st and October 15th, I’m going to wait until October 15th, even though I’m intrisically motivated and understand the importance of receiving teacher feedback in order to improve. I’m okay with not deducting marks for late work, but I still think there needs to be a real perceived penalty in place for not meeting a deadline, and I think that as long as students are required to complete a credit within a specific time frame and as long as teachers are required to submit “marks” at regular intervals, we need to keep deadlines. I also think teachers need the flexibility to extend deadlines or provide individual extensions depending on the circumstances of the student. I hope Mr. Cooper wouldn’t disagree with that. I’m very tempted to email him and ask.

I would also like to ask him some more specific questions about designing down and the Ontario curriculum for secondary English. Specifically, I’d like to know what he considers the Big Ideas to be for specific courses. As I’ve probably said before, it seems much easier to come up with a Big Idea for a subject like history than it does for English.

And yes, I did get him to sign my book, but so did Heather. So there.

Why the Essay?

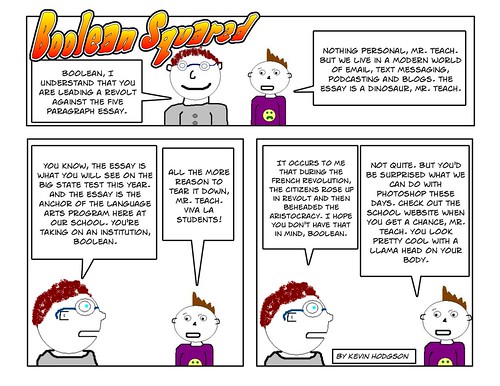

Boolean Squared by Kevin Hodgson

So I’ve decided to declare war upon the 5 paragraph essay–which is perhaps bad timing, given the fact that I’m about to head out to a school where some 7/8 teachers are doing teacher moderation of 5 paragraph essays. Nonetheless, war has been declared and alliances have been formed and well, it’s just hard to stop that ball once it gets rolling. Just ask that poor Serbian nationalist who assassinated the Arch Duke Franz Ferdinand.

Why have I decided this call to arms is necessary? Please read the following manifesto:

Like a virus, the five-paragraph essay infects almost every student, starting as young as grade 4 with some students and continuing each subsequent year until grade 12, and then if the student has survived the virus, sometimes college and university.

Why do we hold this writing form aloft as the pinnacle of academic achievement?

It’s formulaic, repetitive, restrictive, and forces students to purport themselves as experts on a topic they can hardly be experts on.

It doesn’t allow for creativity, questioning, divergent thinking, or personal voice (“Never use ‘I’ in an essay!!”). Is that really the kind of thinking we want to encourage among our students who will be one day venturing out into a future we can’t even begin to imagine?

I am all for encouraging students to explore ideas and support those ideas with evidence, but why oh why does that have to be done in an essay? Or at least this kind of essay.

Because it’s in the curriculum expectations you say?

Where? Show me. I dare you.

The essay does not appear as an example in the Ontario language curriculum document until grade 9 Academic English. And even then, it doesn’t say “By the end of this course all students will write an essay.” It says “By the end of this course students will identify the topic, purpose, and audience for several different types of writing tasks (e.g., … an expository essay explaining a character’s development in a short story or novel for the teacher)” That doesn’t actually say that the student needs to write the essay, just identify the topic, purpose, and audience for the essay.

Some may argue that the essay should still be taught because it is an important skill that they will need in later grades or in college or university. I’d argue that essay writing itself is not a skill. Critical thinking? Paragraph construction? Supporting ideas with proof? Elaborating? Brainstorming? Making connections? Yes. All skills. And they are all necessary to write a cohesive essay. I argue that these are the things we should focus on. Not the essay. These skills are all necessary for a variety of types of writing.

So, comrades, please take up the banner and join me in my fight to find more engaging and creative writing tasks for our students. Do not submit to the facist authority of the almighty essay.

And while you’re at it, here’s some supplemental reading:

Three reasons why the five-paragraph theme is a bad thing

Alternatives to the Five-Paragraph Essay

Assessment and Evaluation Blues

Feeling angsty about this topic. Decided to blog it out.

For a recap of the situation that has given birth to my angst, read my previous post.

I understand current theory about assessment and evaluation. I’ve read Wiggins and Stiggins and McTighe and Cooper. I’ve written and spoken–with great certainty–about designing backwards, “not rehearsing it if it’s not in the play”, and assessment for learning vs. evaluation of learning. So why is it that when I sit down to put together a sample summative assessment task for grade 10 applied English (a course that I’ve taught a number of times) I get stuck? It’s driving me crazy.

In an attempt to figure out why I’m stuck, I’m going to be metacognitive (and slightly schizophrenic) here and outline my process and then try to figure out where I’m going wrong.

I pulled out the curriculum expectations and studied them to try to get a sense of what the big ideas are in the course. Ah, well here’s the problem with that: There are too many expectations! I know that, which is why you have to use your professional judgement to decide what those big ideas are. Right. And how did that work for you?

Not very well. They’re all very vague (which should be a good thing because it allows for more professional judgement) but it makes it pretty hard to pull out a big idea. For example, here are the overall expectations for the Oral Communication strand:

1. Listening to Understand: listen in order to understand and respond appropriately in a variety of

situations for a variety of purposes;

2. Speaking to Communicate: use speaking skills and strategies appropriately to communicate

with different audiences for a variety of purposes;

3. Reflecting on Skills and Strategies: reflect on and identify their strengths as listeners and speakers,

areas for improvement, and the strategies they found most helpful in oral communication situations.

What do I do with that?

Well here’s what I did with that: I tried to figure out what how you could create an essential question for each of the strands, but before I could do that, I started to think, “Hey, if it’s an essential question, shouldn’t it cross strands?”

So I looked at the other strands too and came up with something like: What rights and responsibilities do we have as both consumers and creators of information?

I was quite pleased with that question. Then I started to think, how is this an essential question for 2P English? Isn’t it an essential question for all English courses? That was a little paralyzing, so I tried to move forward and thought, what does it look like to use that question to guide the curriculum planning?

Well, quite frankly, it’s not a very engaging question. It puts a very preachy spin on everything, and when you go back to look at the criteria for an essential understanding, I’m not sure I could say that it IS essential for a 2P student to understand that they have rights and responsibilities as consumers and creators of information.

When I went back and looked at what the 2P English teachers thought were essential for their students the list included: being able to support opinions with facts, write a proper paragraph, cite their sources properly, etc.. First of all, those are all writing expectations and writing is only one of the strands in English. Second, they’re all skills. What’s wrong with that? Isn’t that what we want from our students?

English isn’t just about skills! That came as a bit of a revelation to me after spending that last 9 months looking at literacy skills. I have a slight case of tunnel vision. If we reduce English to a skills course, we suck the soul out of our discipline. Why do people read? Why do they write? Why do they speak? Why do they create? It isn’t just to develop skills. It’s about power and personal expression and a desire to make and see connections.

But how do I justify that as an essential understanding? By the end of this course, it is essential for students to understand that communication is what makes us human. That’s a pretty heavy cross to bear. Yikes!

What I’m stuck with now though, is the summative task for 2P English. What do I want the students to understand and be able to do and what will the evidence be? I have mindmaps and half-completed charts with coded expectations and big questions covering my desk and I’m no further ahead. Why is this so hard?

Sigh. If you’ve got this figured out, please tell me.

Why would teachers want to use Twitter?

Here’s a hilarious little video that perfectly articulates why I use Twitter. Thanks to one of my favourite people to follow on Twitter, Alec Couros. Thanks, Alec!

Getting Off the Comfy Couch

I’ve been thinking about the “comfort zone.” I regularly hear teachers say (and I admit I’ve probably said all these things), “I love teaching that unit” or “I couldn’t give up teaching that novel. I love it!” or “I don’t want to teach that because I’m not comfortable with it.” I’m not saying that there’s anything wrong with loving the content you are teaching or the strategy by which you teach it, but at what point should we step outside our comfort zones and ask ourselves, “But what are the kids getting out of it?”

Just because we love something, doesn’t mean our students will or that it’s necessary for them to love it in order to be successful.

That being said, many of my interests were shaped by the interests and passions of my teachers. Would I have fallen in love with the writing of Margaret Atwood were it not for Mrs. Harvey? Would I have found Jungian psychology remotely interesting were it not for Mr. Williams? Would I have developed such a viceral dislike for Ken Danby were it not for Mr. Hammel? Maybe. Maybe not. I was quite the people pleaser as a student. I dove into subjects and topics that my teachers showed an interest in because I wanted them to take interest in me The by-product was that I studied hard and asked a lot of questions. Maybe not the best example of intrinsic motivation, but it worked for me.

The thing is, most of the students we teach are not like us. One of the reasons we are teachers is because we were pretty successful at the game of school. I think sometimes we forget that. We get frustrated when our students aren’t like us. But why should they be like us?

Okay, okay, so my point: Every day we expect students to do things that they don’t love or find comfortable or even relevant, because we think these things are important. We accept the idea that it takes time for a student to master a new skill, and that a student might not find something interesting, but it’s still important for them to understand that thing (I should mention I’m not talking about the curriculum expectations here, but they way we approach those expectations. Nowhere in the Ontario secondary English curriculum document is the study of Hamlet mandated. Even though I love it.).

How often do we ask the same of ourselves?

Why should we only teach things that we find comfortable and familiar? Why should my love of A Streetcar Named Desire earn the play a place on my syllabus? I think you can make a case for saying that if a teacher is truly passionate about a certain piece of text or a certain topic, he or she might do a better job teaching with it. I just don’t think that personal taste should be the only deciding factor when it comes to choices about teaching.

More importantly, I think we should step outside our comfort zones every once in a while and ask ourselves, “Do the kids find this as engaging as I do?” and if the answer is no, “Is there another way that I could meet this curriculum expectation that the kids would find engaging?”

And why not think about letting our students teach us something for a change? After all, we’re in this for them aren’t we?

Photo credit: emdot

Doing more with less

Then I realized, maybe this could be an opportunity. Maybe this will be the push teachers and administrators need to stop trying to ban cell phones and mp3 players and see them for the potential learning tools they are. Maybe we can’t afford a class set of clickers, but most of our kids have cell phones they can use in conjunction with something like polleverywhere.com. Can’t afford a class set of digital cameras? Most of your kids already have them.

Thanks to Mike for his thoughts below:

Necessity is the mother of invention. Right?

Stupid Rules

This post actually has next to nothing to do with technology for a change. My husband and I got into a bit of a debate last Friday about rules. We were talking about things like cell phone bans and no-hat policies, and I said that if the rules were perceived by students as baseless and unjust, then it was unrealistic to expect them to follow. That they would rebel–not because they really really want to wear their hats in school, but to rebel against the rule itself. My husband (also a teacher) agreed that some rules may be “stupid” (my word) but that it was a slippery slope if we said that students had to follow some rules but not others. I see his point, I really do, but at the same time, I was not about start demanding that a student hand over his cell phone because he flipped it out in class to see if he had any messages–even though my school’s policy might have told me I must. It’s just not a hill I’m willing to die on. I have bigger battles to fight.

I’m not saying that students should be allowed to disregard any rule they think is stupid. But let’s face it. There are some stupid rules out there, and to expect students to follow those rules just because we say they are rules offends every fibre of a teenager’s being.

The next logical thing for me is to ask schools to review “stupid” policies. But what do I do in the meantime? If the policy says I must take a cellphone if a student has it out in class after being warned once, but I don’t want to because it’s not disrupting my class, do I have to? Because you know that student might end up telling Mrs. Stickler that Ms. Barker didn’t take her cell phone when she had it in class. I resent other teachers dictating what rules my students need to follow in my class, provided that the students are learning and behaviour is courteous and respectful of me and the other students in the class.

Must I insist that students follow stupid rules?

(I should mention that the rationale behind the no-hat policy is student safety. Hats obscure student faces from security cameras. Although I have to say, in my experience viewing security camera footage, I could never really identify a face. The hats might actually help us identify students!)

Photo credit: Zac Zellers